In my previous posts, I’ve focused on how the Theory of Constraints (TOC) can help you achieve your goals. I’ve also discussed why methodologies like Lean and Scrum can be effective in certain contexts, while also identifying scenarios where they might not work as well. My primary aim has been to introduce you to tools and principles from Eliyahu Goldratt’s Theory of Constraints that can significantly increase your chances of success. If you have any questions or want me to dive deeper into a specific topic from my posts, feel free to reach out via email.

In this post, I want to shift focus and explore the concept of complexity, providing you with a working understanding that will help you navigate the many systems of improvement you’ll encounter in your professional journey.

Inherent Simplicity in Complexity

Last year, Wolfram Mueller wrote a short article titled "If you think your system is too complex - then you are too weak!" [Link to article here]. While written somewhat tongue-in-cheek, the post sparked a huge response, far exceeding the length of the article itself. In it, Mueller explains why the Theory of Constraints emphasizes identifying the one key constraint within a system of interest. He argues that "surviving complex systems typically revolve around one key constraint," and this constraint is often the pivotal point for improvement.

To identify this constraint, all stakeholders must align around a common goal, using it as a benchmark to guide their decision-making. When we look at systems with stable outputs, it often becomes clear that there is one dominant constraint. If this constraint is neither fully utilized nor subordinated by the rest of the system, that’s when we can begin to focus on solving the problem.

Evolution: Understanding Complex Systems

Most systems we encounter in the real world are complex. Their behavior or output is the result of interactions among multiple components. However, many systems of interest (especially in engineering and optimization) exhibit attractors—regions or points in phase space where the system tends to settle. In simpler systems, this often manifests as stationary points where the system's behavior becomes stable.

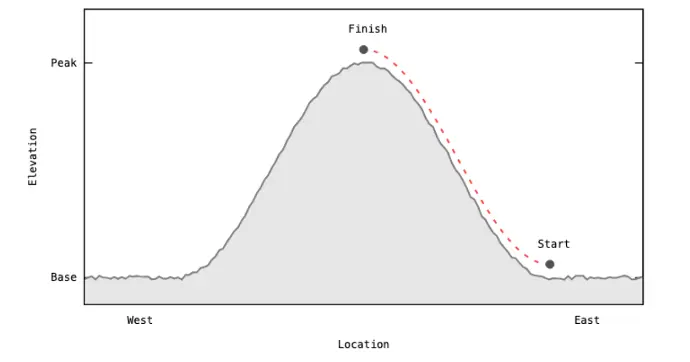

Engineers often model these stable behaviors with linear equations, simplifying the problem to make it easier to solve. For example, imagine trying to "climb a hill" towards increasing height. By following the path of greatest ascent, we might find a stationary point that represents either the maximum or minimum value of the system’s performance.

Hill Climbing toward Increasing Height

This is why linear solutions are so popular—they often work well in many cases and are intuitive to use. When seeking to optimize a system, engineers often apply reductionism, breaking down the problem into smaller, more manageable components and solving each one separately. This approach is especially useful when you’re looking to make small, incremental improvements, or when addressing special causes in problem-solving.

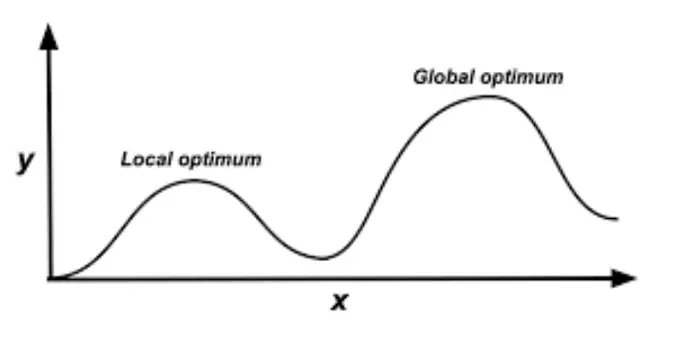

However, linear optimization has its limits. If you aim for the global maximum (the best possible performance), there’s a risk of getting "stuck" at a local maximum, as illustrated by the concept of hill climbing. If you only focus on small, incremental improvements, you may miss the potential for much larger, more impactful changes.

Getting Stuck at Local Optimum

Revolution: Unlocking Revolutionary Improvements in Complex Systems

On the other hand, complex systems have the potential for revolutionary improvements. By seeking broader changes, we can achieve massive improvements that lead to hyper-productivity. The key here is iterative optimization, where we continuously adjust and adapt the system in search of new peaks or extrema.

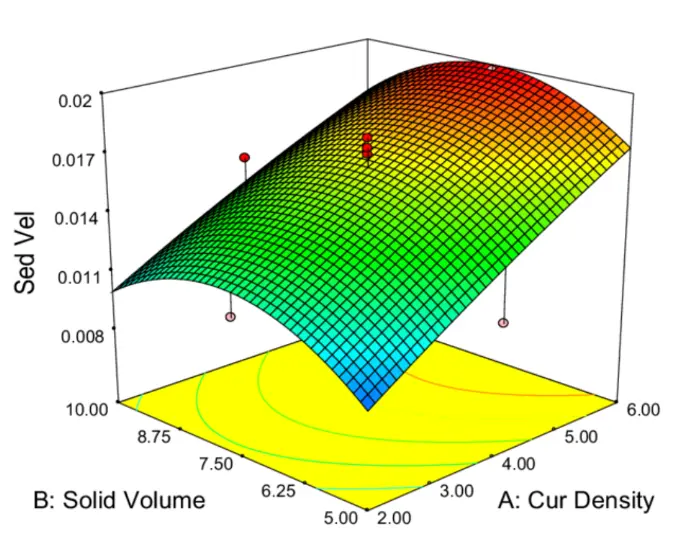

In a complex system, improving the constraint often requires tackling common causes of variability. One powerful method for optimizing physical systems with multiple variables is Design of Experiments (DoE), which allows for simultaneous adjustments of several parameters to find the best possible combination.

Finding the Peak with DOE